By Susan Armitage

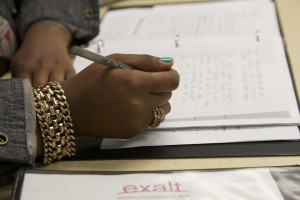

On a recent Friday, 16-year-old Makala was dressed fashionably in yellow skinny jeans and a trim black jacket. But choosing her outfit was a luxury. So was the home pass that allowed her to leave The Children’s Village in Dobbs Ferry, N.Y. Until recently, most days Makala wore khakis and a green shirt to satisfy the dress code for her 10-month detention sentence.

Since her first arrest at age 12, Makala has bounced through a number of detention and transition programs. In an interview a few weeks before her mid-April release, she was eager to leave an environment she described as plagued with constant threats.

“Boys don’t start a lot of problems,” she said. “Girls, they always seem like they have a point to prove.”

While the majority of youth offenders are male, the juvenile justice system is dealing with more and more girls. In 2010, girls made up 29 percent of all juvenile arrests nationwide, and though juvenile crime rates are dropping overall, the decrease is less marked for females. Like their male counterparts, girls in the system often have troubled pasts, histories of abuse and mental health issues, researchers say. And while few studies have been done on female offenders, some researchers believe the long-term consequences of delinquency may be more serious for girls than for boys.

Delinquency cases for girls have skyrocketed in recent decades, increasing 92 percent between 1985 and 2002. It’s unclear why females now make up a greater portion of juvenile arrests than in the past, but changing attitudes around gender may play a role. When Deborah Lashley started working in the juvenile justice system 20 years ago, she said, girls were less likely to be remanded and sentenced than boys or got lesser sentences for the same crimes. She sees a difference today.

“There was more that kind of paternalistic view of them,” said Lashley, who manages the Girls Re-entry Assistance Support Program (GRASP), an initiative of the Brooklyn district attorney’s office. “Now I think people are beginning to realize that females can be just as dangerous or violent or problematic as the males.”

Makala didn’t want to talk about what got her into trouble, but like many girls in the system, she had problems at home. During her time in detention, she thought a lot about the influences in her life. “If my mom wasn’t raised in a happy home, I can’t expect that home to be happy,” she said. “I have to work around or work with my mother, teach her how a family’s supposed to be.”

Female offenders are more likely to suffer from mental illness than male offenders and report being victims of child abuse at greater rates. A quarter of girls who commit violence have been sexually abused, while the rate is only 1 in 10 for nonviolent girls, University of California, Irvine psychology professor Elizabeth Cauffman noted in her paper, “Understanding the Female Offender.”

Girls also tend to place a higher value than males do on personal relationships, which can fuel assaults that get them in trouble. “With females, you find that it’s usually somebody they know, whereas males often will take random victims,” Lashley said. “It’ll be over a boy, over something they said, it’s a relative.”

On the inside, conflicts are also common. Different detention programs may be co-located in the same building, breeding suspicion. “The girls see each other, they don’t know them, so they’re looking at each other, they start snickering, they start laughing, then a fight breaks off,” Makala said.

Research findings are mixed on whether girls are treated more strictly by the system. But in Makala’s experience, boys in detention get more privileges, such as home passes, and staff members are harder on the girls. “You’re not supposed to be in the jail,” she said. “You’re supposed to be at home, acting like a lady.”

Lashley said changes are needed to serve girls effectively in a juvenile justice system designed for boys. Her program takes a gender-sensitive approach by building supportive relationships and safe spaces for girls to talk about their problems. “Females and males socialize very differently,” she said. “It’s taken time for the system to come around, to understand that to really rehabilitate females, you need things slightly different than you do for males.”

As juvenile offenders grow up, marriage and parenthood tend to have a stabilizing influence on boys, Cauffman writes, but not on girls, who often pick mates involved in illegal activity. And without adequate support for females coming out of the system, the instability that drives juvenile delinquency is more likely to be passed on to the next generation.

Lashley said changes are needed to serve girls effectively in a juvenile justice system designed for boys. Her program takes a gender-sensitive approach by building supportive relationships and safe spaces for girls to talk about their problems. “Females and males socialize very differently,” she said. “It’s taken time for the system to come around, to understand that to really rehabilitate females, you need things slightly different than you do for males.”

As juvenile offenders grow up, marriage and parenthood tend to have a stabilizing influence on boys, according to “Understanding the Female Offender,” but not on girls, who often pick mates involved in illegal activity. And without adequate support for females coming out of the system, the instability that drives juvenile delinquency is more likely to be passed on to the next generation.

Makala is determined to break the cycle of negative behavior she experienced growing up. She’s transferring to a boarding school in Brooklyn this fall and has her sights set on college. She plans on becoming a behavior therapist for troubled youth.

“Fighting, people stealing, people yelling at each other, people not caring, just leaving you,” she said. “It’s all you’ve seen your whole life, so that’s all you know. But if you break away from it, then you could change the whole pattern, so when you have kids, your kids don’t have to go through that.”